First time entrepreneurs generally lack the experience to build business models that are not only scalable, but also profitable in the long run. From the early startup boom of the silicon valley till today, this has been the pattern almost everywhere in the world. However, in the past decade, incubators and accelerators/investors across the world, have slowly but surely tried to fill this gap. While incubators help early-stage entrepreneurs with mentorship, investors help in accelerating the development through capital.

First time entrepreneurs generally lack the experience to build business models that are not only scalable, but also profitable in the long run. From the early startup boom of the silicon valley till today, this has been the pattern almost everywhere in the world. However, in the past decade, incubators and accelerators/investors across the world, have slowly but surely tried to fill this gap. While incubators help early-stage entrepreneurs with mentorship, investors help in accelerating the development through capital.

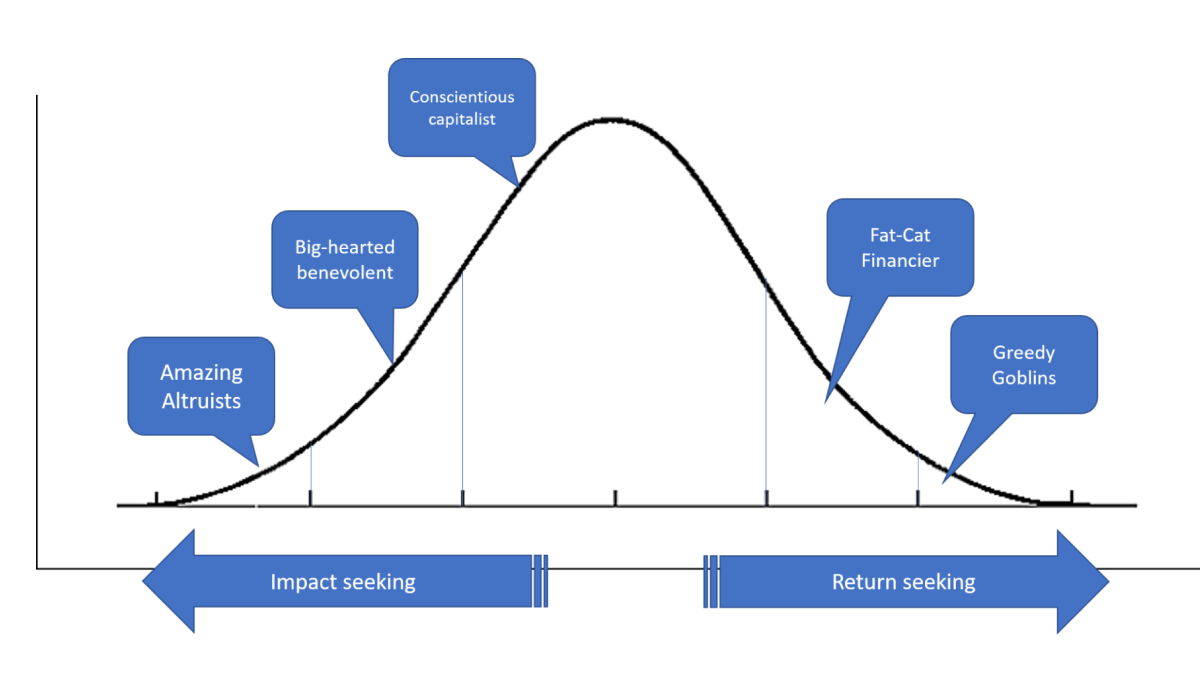

But the catch for the entrepreneurs has been to find the perfect incubator-investor combination. Incubators to help them shape their business model and the investors to back their business through funding. This is especially difficult in the social entrepreneurship universe. While Villgro was founded in 2001, Menterra, its partner investment fund was set-up in 2016. Together, this platform provides a strong value to early-stage entrepreneurs. The platform works like a well oiled conveyer belt and enables a business right from its formative stages to growth.

To know exactly how this model works, I caught up with Paul Basil, Founder & CEO, Villgro and Mukesh Sharma, Co-Founder & MD, Menterra Venture Advisors. The duo explains how one of their flagship portfolio companies, Biosense, achieved success, and is now creating impact at scale.

THE BIOSENSE STORY

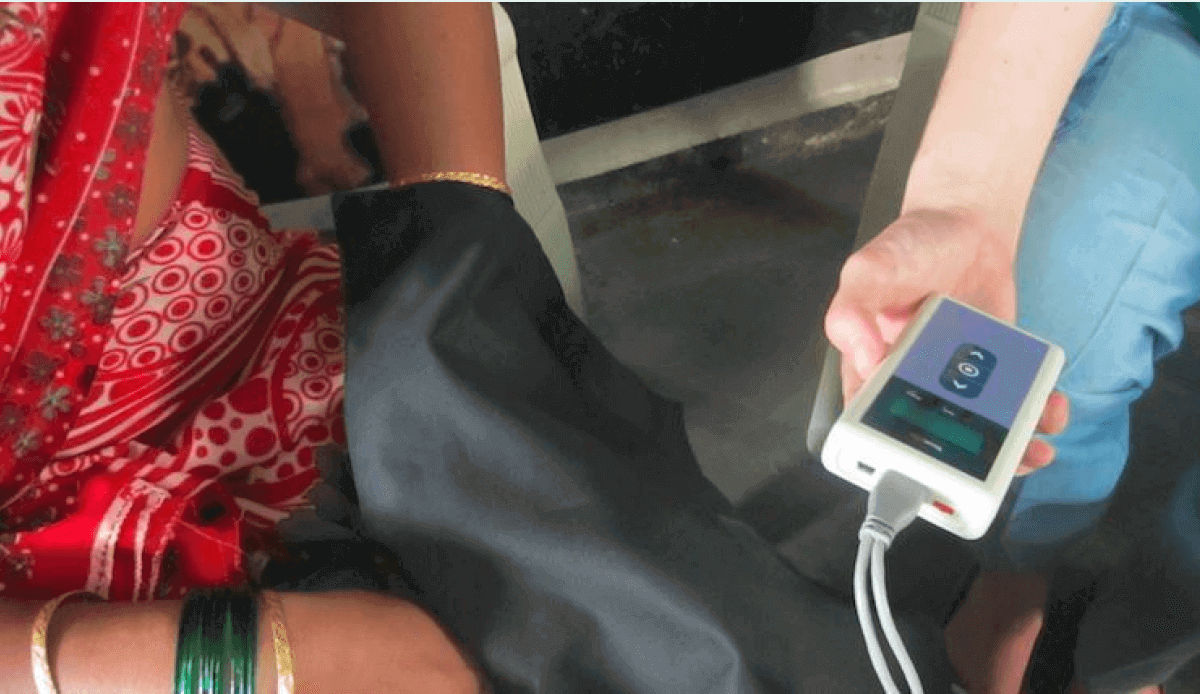

Biosense is a cutting edge IoT product that is focused on tackling India’s twin challenges — malnutrition and diabetes. The product leverages connected devices to increase accessibility of tests. From the hilly regions of Ladakh to desert districts of Rajasthan to the tribal areas of Gadchiroli in Maharashtra, Biosense has been catering to some of India’s poorest, in diverse geographies.

It can be hard to believe that Biosense was just a dorm room startup!

“When we incubated Biosense, it was a product idea and the founders were still pursuing their degrees at IIT Bombay. It was a typical dorm startup!” recalls Mukesh. “The founding team told us they know the problem and they can create solution. They didn’t know how to build a business around it. They asked us if we would help them to build a business. It was a test of our incubation model. Over the last 7 years, Biosense has launched 7 products and has raised more than USD 4Mn.”

~ All Biosense devices use mobile platform with geo tagging and cloud-connectivity enabling data on disease

prevalence by village and district.

~ Potential Aadhaar integration would enable care to high risk patients.

~ Government and corporate initiatives are now able to use this data to provide targeted intervention resulting in

efficient usage of scarce resources.

INITIAL CAPITAL AND TALENT DEVELOPMENT

Apart from the infrastructure setup costs, hiring the right talent is the first major hurdle for any startup. While speaking about tackling this, Mukesh Sharma says “We helped them build a team and business around their passion and idea. So, the Villgro-Menterra partnership with Biosense can be summarised in one line: transforming a dorm startup into a solid organisation that delivers impact at scale.”

Mukesh elaborates, “We helped them raise first angel and VC round. Once we launched our fund, we provided more than USD 1Mn in equity funding. For working capital, soft debt funding of more than USD 2Mn was arranged through our investor network. Capital was an initial impediment. There was need for very intense hand-holding in multiple areas.”

“We worked on talent development at all levels (CxO, board and the execution team). Building sales DNA and engine has been an area of focus for us. We engaged distributors and mentors from large pharma companies to provide them with very specific commercial, distribution and sales inputs. We formalized the board and initiated robust governance structures. We helped team of doctors and engineers develop a business aptitude with sound financial discipline.”

EXIT FROM VILLGRO AND HANDOVER TO MENTERRA

Villgro initiated the incubation of Biosense back in 2012. Initially, it focused mainly on a strong product and smart customer insights. But later on, after about 4 years – in 2016, we wanted Biosense to become aggressive in the market. That’s when Menterra entered the fray.

“From a friendly, caring Villgro there was a shift to a more aggressive Menterra. This taught us a lot at Villgro that we need to be harder and tighter with our entrepreneurs, while providing them the shelter to kickstart their businesses.” Paul says while talking about the transition.

Mukesh also has fond memories of those days. He recounts, “Our journey started 7 years back. The trust was already established at Villgro but there was more tough love at Menterra. They knew that we only have their best interests in mind. So, our relationship evolved but the trust and mutual respect remained. That helped through difficult times that every enterprise invariably goes through.”

WHAT THE FUTURE HOLDS FOR BIOSENSE

The mentoring through the Villgro-Menterra platform has helped change the DNA of Biosense – from being a tech & product-driven to a market-focused organisation, according to Mukesh.

He continues “When Biosense joined Menterra, its revenue was ₹1.5 Crore. Within 3 years it would likely be at 10x in a segment where fewer companies have built serious domestic business. It is also an important Make in India story and is well aligned with the development challenges and priorities of the country as well as the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Our focus is to help them scale. For that, the level of intensity and engagement needs to and continues to remain high.”

THE VILLGRO-MENTERRA PLATFORM

Paul Basil is excited about the future of other similar prospects like Biosense. “We are extremely delighted to see a company that has travelled through our ecosystem in form of the incubator (Villgro) and investment fund (Menterra). To build successful companies, incubator and downstream investors need to partner and work together. This alignment is very weak in our current funding and support ecosystem. Investment Funds wait for good quality companies to emerge. Entrepreneurs and incubators toil hard to build investable businesses. To fill this gap, we need serious collaboration. A closely aligned incubator-investor partnership like Villgro-Menterra can go a long way in building a strong and vibrant startup ecosystem in India.” he concludes.

Learn more about the impactful, innovative and successful enterprises that we are creating at www.villgro.org and www.menterra.com.

If you are an early stage entrepreneur and want to be supported, please connect with us at info@villgro.org.