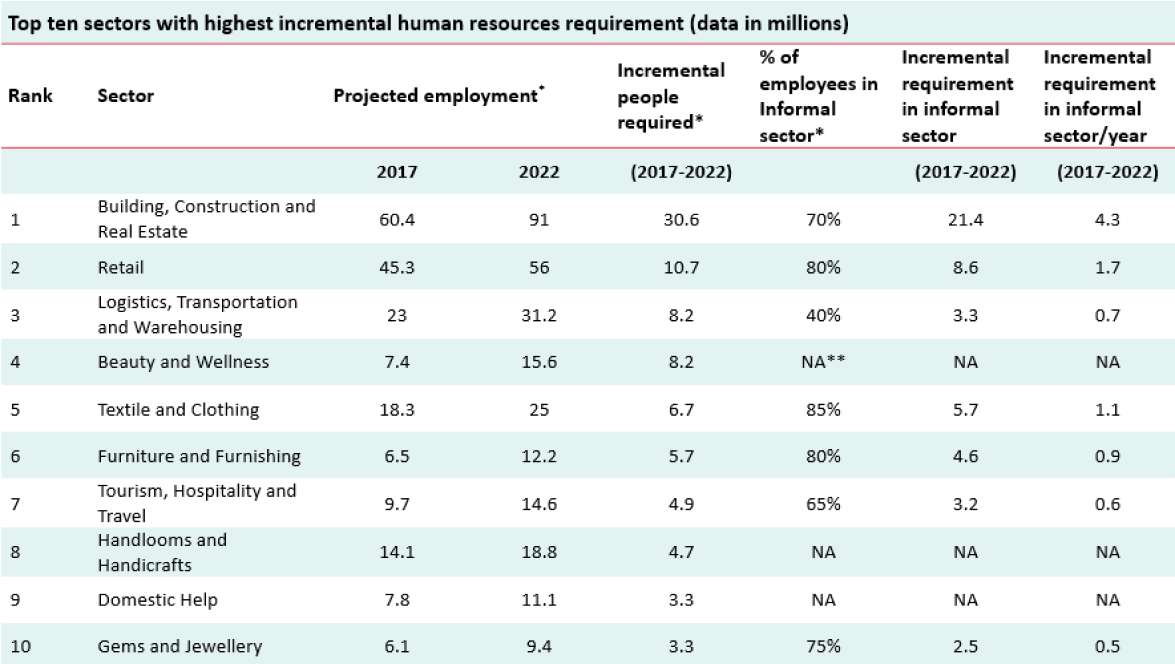

New jobs created over the next five years will be largely in the informal sector. Therein lies the opportunity to skill the informal workforce, enhance their wages and enable their transition to better jobs and micro-entrepreneurship.

The Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship has projected a total human resource requirement of 103.4 million people between 2017 and 2022. Interestingly, a subset of industries is going to create a disproportionate number of these new jobs, with more than 85 million coming from the top ten sectors, one-third of these in construction alone.

One of the key engines of this growth will be the informal workforce; with three industries alone employing more than one million informal workers each per year for the next five years (see table below). Besides the obvious areas of growth like construction and retail, sectors like tourism and hospitality, furniture and furnishings, and warehousing and logistics will each add more than 500,000 informal workers every year.

The following table projects the informal workforce requirement through 2022.

With so many people entering the workforce over the next few years, we have an opportunity to either bring them into the formal economy, or enable a large number of them to have choices and leverage to command higher wages; and, if they choose, become micro-entrepreneurs.

One size does NOT fit all: Selecting the right model for the right industry

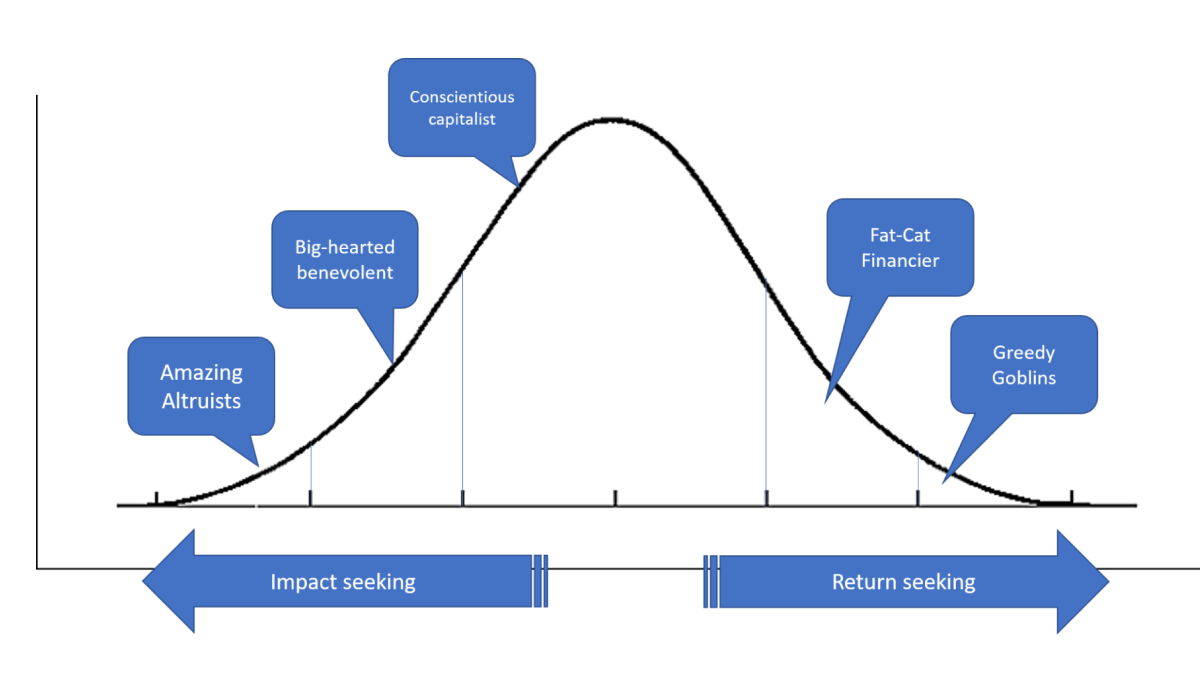

There have been many models over the years to match the demand for labour at varying skill levels, and the supply of employment opportunities. A recent industry report highlighted four potential business models that could help improve outcomes for workers:

1. Self-employment model: In this model, the skilling company offers training to students who in turn, graduate with the required experience to get a job or possibly start their own business. The company’s revenue comes from fee-paying students, or from a government or a nonprofit client. For example, NSDC has partnered with deAsra Foundation to develop and deliver entrepreneurship skills training.

2. Market linkage model: The market linkage model is one where self-employed workers are matched with open jobs resulting in enhanced wages for some, and new employment for others. In recent years, these marketplaces have become familiar to many of us; examples include Uber, UrbanClap, Betterplace, and so on.

Two important conditions are required for this model to be successful. First, a ‘virtuous cycle’ between supply of workers and demand is needed. In Uber’s case, a high number of drivers leads to more customers joining Uber, which in turn leads to more drivers, and so on. If either side becomes weak for an extended period of time, the other side will start dropping-off.

Second, a basic level of technology comfort is usually required for all users. Else, the marketplace will require infrastructure and resources to assist with the onboarding – for example, Bharat Matrimony and Babajob.

While these two models relate directly to opportunities in the informal sector, there are two more approaches that are increasingly being used to place people in informal jobs. These are the employer- and placement-led models—traditional skilling models that have mainly been used for formal jobs till date.

3. Employer-led model: In this model, training is offered to students for a skill required by a specific employer. These students may be new hires or current employees who are ‘upskilled’.

Maruti Suzuki, India’s largest car-maker is setting up 400 skill training and enhancement facilities, in partnership with its vendors, with vendor-partners investing in the set-up of these facilities. The company itself has not made substantial additions to its own staff in the recent past; however, through its production of 1.5 million cars annually, it estimates that it creates up to a million informal jobs downstream — in driver training, repairs, insurance, and so on. According to R C Bhargava, chairman, Maruti Suzuki, “Economists and policymakers seem to underestimate the contributions of the informal sector in creating employment”.

4. Placement-led model: Here, the skilling company has a number of employer-clients where trainees can be placed. Like the employer-led model, it is well-suited for growing industries with multiple players that all require a specialised skill. Ancillary health services company Virohan has a placement-led model where trainees pay to become X-ray technicians and get placed at hospitals that work with Virohan.

THERE IS A GROWING REALISATION THAT THE LINES BETWEEN FORMAL AND INFORMAL JOBS ARE BECOMING POROUS.

The employer- and placement-led models are increasingly being used in the informal sector as industry leaders are beginning to recognise the role played by the informal sector in driving their own productivity and output. There is a growing realisation that the lines between formal and informal jobs are becoming porous and therefore, a lack of skills in the informal sector—similar to a lack of skills in the formal sector—will have implications on larger, established companies as well.

Deciding which model works best: A framework for social entrepreneurs

For social entrepreneurs, it is critical to match the business model to the industry. In some cases, current industry dynamics may not allow for conversion of informal to formal workers, and entrepreneurs may want to focus their energies on a different sector. Some questions to ask yourself for each of these models include:

- What are industries in which the demand, visibility into open jobs, and increased income make self-employment a reasonable return on investment (ROI) for people currently headed for the informal workforce? How would fee financing work in this model?

- Do market dynamics on the demand side and profiles of the workers on the supply side make a market-linkage model possible?

- Which sectors require high capex and fixed costs for training and do they have sufficient margins to make an employer-led company viable?

- Is there a large enough network of accessible businesses for the placement-led model to work?

Matching industry to business model

To better understand how to match an industry to an appropriate business model, we’ve described two examples below.

Building, construction and real estate: market linkage and placement-led models

From the NSDC data presented earlier, construction is by far the largest employer of informal workers, with more than four million new jobs added each year. Yet, the overwhelming majority of construction jobs over the next five years will remain low-skill.

The profiles of most workers in the construction industry and relative commoditisation of their skills makes it difficult for a market linkage model without a major established player backing it. Therefore, instead of initially focusing on the large majority of low-skill jobs, we suggest applying the market-linkage model for the approximately 10 percent of construction jobs that are skilled jobs (and not completely commoditised). These may include electricians, plumbers, carpenters, bar-benders, masons, and welders—jobs for which there would be competition when placed on a marketplace.

However, market-linked models take time to get off the ground and require a pre-existing set of qualified workers. A placement-led model that first organises and builds a track record of placement might be a good first stage. Eventually, the graduates of that programme could migrate to an open marketplace.

Auto and auto components: employer- and placement-led models

The auto industry currently employs more than 19 million workers and expects to add another 2.2 million by 2022. With more than half the industry workforce in the informal sector, the auto and auto components industry is an opportunity to formalise over 200,000 employees each year over the next three to five years.

At present, automotive skilling is undertaken by the Automotive Skills Development Council (ASDC). Manufacturing companies also have centres of excellence for their workers, while auto component makers and auto dealers work with original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) to train workers. There are many characteristics that make an employer-led model interesting for entrepreneurs seeking to create an alternate and more efficient system:

- There is a higher degree of skilling required than in most other sectors.

- This sector represents an aspirational step from other manual sectors like construction.

- There is a relative lack of trainers today vis-à-vis the expected growth.

- Infrastructure cost is high and technology is changing fast.

- Companies want to outsource training to reduce costs and keep up with the latest trends.

In time, a placement-led model may also work. Currently there are challenges owing to lack of standardised curriculum, students’ inability to pay for such trainings, and rapid changes in technology, which make the capital investment tricky. However, student-financing options are becoming available from new companies, and we have seen the placement-led model work in other sectors with similar characteristics such as healthcare.

As the train-and-place model gets proven via employer-led programmes, and the industry views this as a critical channel for scale, we can expect viable placement-led models to emerge.

WE ARE ENTERING A TIME WHEN EFFECTIVE ENTREPRENEURIAL VENTURES CAN UPSKILL MILLIONS OF PEOPLE IN THE INFORMAL SECTOR.

We are entering a time when effective entrepreneurial ventures can upskill millions of people in the informal sector. By identifying pockets of opportunity in growing industries and marrying them to the right business models, the earning power of millions of workers in the informal sector can change significantly.

The net result will hopefully create a new segment of people that have the opportunity to build a career instead of spending their working lives looking for the next job.

We want IDR to be as much yours as it is ours. Tell us what you want to read.writetous@idronline.org